[ad_1]

In this next phase of modern commerce, deeper and more seamless interconnections are being pursued to further optimize consumer experience. Financial institutions have been the historic underpinning, and so it’s getting especially interesting for them.

The consumer is motivating all of this. Our purchasing experience has become more complex, omni-channel, contextual, and digital first, and business has followed. Merchants (or vendors) need to rediscover their customer experiences, newly accommodating the journeys they increasingly prefer and evolving with their newly dynamic preferences.

The modern consumer journey deconstructs the niceties of traditional containment within the merchant’s own store. It frequently crosses or is embedded within other merchants, and it may extend beyond various digital platforms, to include non-digital and even offline segments. The journey also may be spread out more across time and space, in ways that technologists need to account for.

While changes in consumer tastes and habits is the motivator of all this, they have meanwhile been pushed along by technology. Economies are at the cusp of moving beyond being cashless, to what’s next. Consumers have responded by demanding an experience that is ever more streamlined and immediate, a direction that is carrying commerce along with it.

To the merchant, connected commerce is an enabler. It improves satisfaction for current customers and opens up innovative strategies to increase conversion and bring in new business. An obvious example are the digital to brick and mortar models such as Target’s pick up (BOPIS) service. Going further is the idea of Phygital, the inseparable physical and digital worlds where all brand experiences lie. Even more enticing is the ability to capture customers across partners, for example, what if King Arthur flour could follow you from their site into the supermarket, with relevant offers at check out? (A little scary.) Or what if you wanted to check the status of your white labeled credit card not with the issuing bank, but with the label? Or perhaps you spot a great bathing suit on social media and want to buy it?

All the examples above could be accomplished with one-off system integrations, but connected commerce is a new idea, partially because its a new way of doing these integrations. Done right, it enables greatly reduced onboarding and transaction costs. The less friction, the lower the cost of each new opportunity and, as costs get lower, services can become ever more pervasive. Here’s a great overview of just a few opportunities from vendor P97’s perspective:

Connected commerce results in use cases that are qualitatively different for consumers. You can increasingly fulfill anywhere, and on the consumer’s terms. Expanding on the Target example above: what if I’d ordered for pickup on my app only to realize, enroute to the store, that I forgot to order something? I’d just call up Target’s system on my car and add that new item to my order. That’s the promise of connected commerce, a concept that emerged alongside the related connected economy. Connected commerce may one day be synonymous with ubiquitous commerce, such as the ability to communicate with any vendor at any time over any channel, with no prior setup.

Connected commerce is a constellation of approaches. These may include warehousing and process revisions, enhanced partnerships and most of all, a revised digital component that enables low friction interconnection with new channels and partners. Exactly what’s needed depends on the use case. Here are some considerations for the design of a “Connected Commerce” strategy:

- Build for evolution, because channels and partners are ever evolving. Often this means defining basic services that can be reincorporated in various ways, and it certainly means building a structure that is able to evolve.

- Can services be provisioned in a way that can be highly customized for end users? This includes custom flows, multicurrency and branding.

- Define and validate the business case. It may sound strange to say, but don’t get carried away by the vision of connected commerce. Stay grounded and find the balance that works for your business, proceeding cautiously if necessary, to validate that consumers will come to what you build. Oftentimes this isn’t necessary, because connected commerce arose from the realization that consumers are staking out new territory ahead of the ability to support them.

- Insure service delivery is consistently experienced across channels and any other dimension of the consumer experience. This includes provision of all relevant use cases across channels: not just purchases but returns, cancellations, account queries and anything else a consumer expects to do.

- As the consumer experience may cross channels and vendors, expectations around marketing and branding may need to be updated. You might have to surrender some of your brand identity, loaning that honor to the consumer-facing partner in the transaction.

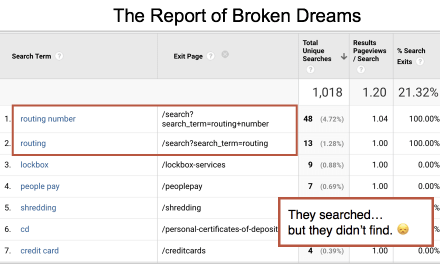

- You will need to update metrics collection or you won’t correctly record things like conversion, site exits and many other factors intended for previously walled gardens.

- Security is a prerequisite in connected commerce. This can be handled by partnering with back end institutions that are structurally adept at security, particularly across regulatory environments, i.e., banks and other large financial institutions. Industry-standard authentication and authorization have been key enablers of connected commerce. So too are evolving card and biometric technologies for use at PoS and other IoT edge points. Increasingly, interactions will be machine to machine. With so much more occurring at the edge, real time fraud detection is critical.

There is a technical consideration underpinning much of what’s happening: the application programming interface (API). Public tech APIs have been around for a generation and the evolution of these in some way set the stage for connected commerce, along with industry-wide authentication and communication standards.

The major use cases within connected commerce have thus far been financial. One might assume that the providers most capable of enabling connected commerce are those who have have long been deeply involved in the security and regulatory environment of financial transactions: financial institutions such as bank and credit card companies. And yet, many institutions gained their internal capabilities by accretion, over many years. While their systems need to work as one, many are currently siloed and mismatched to the external API-first services that are de rigueur in connected commerce.

The transactions ecosystem is rapidly changing, and banks in particular must either adapt or lose not just new business, but existing business. Consumers first migrated away from the physical branch, then migrated from the ATM towards cashless, and there are strong signals that consumers want their banking services contextually, divorced even from the bank’s brand identity.

In aligning to the need, financial institutions at least need to ask:

- What is the extent of cannibalization in existing consumer relationships for each new relationship, and is it justified? This cannibalization will balanced against the lower acquisition cost of new business, new revenue streams, and meeting the competition.

- Can legacy systems be bent into shape to support the mission, or will some require an update to be fit for purpose?

- How can consumer identity be insured and then transferred across channels?

- How can partner vendor onboarding be minimized under as many scenarios as possible?

- How can consumer onboarding and transactions be handled in an automated fashion, which may impact KYC, credit approval, and more.

- How can the linkup of banking services, such as payments and account access, with merchant platforms be made as easy as possible? Developer experience is quite important and shouldn’t be ignored, for example, documentation should be darn near perfect, and an easy self-service experience should be supported, including a turnkey test and validation service.

- Can a consistent experience be guaranteed across channels?

- What are the required SLAs for engaging in real time external transactions.

- What’s the right mix of incentives and payoff across partners — up through the consumer — needed to make things work? See the discussion below on embedded finance to see how calibrating these considerations can be a make or break proposition.

- Does the risk model need to be altered or recalibrated for specific vendors and customer types? Can the vendor’s experience help to inform the risk model?

- What services should go upstream and which should the financial institution be handling?

While legacy financial institutions will more often need to build out support for connected commerce, vendors such as NCR, Oracle and others can offer much of it out of the box, so that smaller players also have a shot.

Much of connected commerce are financial transactions. Embedded finance is the financial industry’s answer to connected commerce. Europe got a head start with the Payment Services Directive (PSD) of 2007 intending to harmonize payment services across the EU while PSD2, adopted in 2015, was aimed at promoting the development and use of innovative online and mobile payments through open banking. In the US, the Financial Data Exchange started up in 2018. In this case, pressure came from fintechs wanting to establish the right to consumer-permissioned data sharing. Ever since, there’s been a digital first explosion that has embedded financial services — lending, payments, insurance and more — in all manner of third-party experiences. And it’s not just digital native consumers that are driving the demand.

The future of embedded finance removes the financial institution from the primary relationship with the consumer, replacing it with a non-financial vendor. Payments has traditionally been the major use case, and also trip and car insurance, and white-labeled credit cards. Newer though already commonplace are purchase insurance (a great example of a contextual experience) and buy-now-pay-later. Embedded banking is a next step, where companies like Lyft can deposit driver payments direct to debit cards. Other embedded banking services offered from within the vendor may include secured and unsecured lending, various card services, accounts and again, payments.

Embedded banking is well suited to a higher frequency of transactions. That level of activity practically mandates that the financial services layer is made transparent in order to minimize consumers’ transaction costs. Lyft is such a high frequency example, as are future applications in microfinance, receivables factoring, and much else. Indeed, you could almost qualify opportunities for embedded finance based on how quickly a given opportunity transacts! Unsurprisingly, the most extensive penetration is highly digitized: comparatively low price retail and e-commerce, along with meal and home delivery, and mobility.

Embedded finance is gradually going to displace a hefty slice of current transactions and creativity is going to drive the opportunity for new transactions. Estimates peg the embedded finance sector at $7 trillion by the next decade.

Embedded banking enhances the value chain, with multiple participants usually benefiting. For example, on Shopify onboard new store owners with relevant banking services, which saves work for the store owner while elegantly threading the banking service into the Shopify experience. Shopify is also better able to qualify new store owners, and their acquisition costs are minimal, so they can offer better terms. Adding value to the store owner is competitively important to Shopify, and encourages more people to try it out.

Banks that have a good current payments business would be wise to qualify and upsell their existing consumers on an expanded menu of embedded finance services.

The architecture for embedded finance typically involves three tiers. The vendor that touches the final consumer is at one end, while a bank is at the other. Banks typically occupy that spot because of their competencies in holding money. Who’s in the middle of this relationship gets interesting, because it turns out banks aren’t necessarily good at serving up the infrastructure needed to connect with a vendor. In Lyft’s case, the infrastructure is provided by Payfare; lump Payfare into the category of a “fintech”, along with Stripe and Apple Card.

At last estimate, most of the revenue in this relationship accrued to the banks, as they tend to bear the risk. But the upstream partners didn’t necessarily like that, and so vendors are increasingly offering banking products, which makes sense as they’re closest to the consumer and so can tailor their offerings. Meanwhile the fintechs are trying to add risk (and therefore gain profit) such as via repo agreements that take risk off the bank’s balance sheet. Fintechs also can exploit domain-specific expertise such as Payfare’s emphasis on the gig economy. That expertise could further translate to better credit, fraud and other models. A capable bank can still cut out the fintech and add a new revenue stream by undergirding the vendor’s banking products.

Nonetheless, banks do face significant risk, as embedded finance threatens to unbundle the banking value chain and also pick off the best consumers through superior knowledge of their downstream interactions. Some fintechs might even be gaining more domain knowledge than the vendors they serve. Unsurprisingly, some of the major banks have been spreading bets by purchasing, among other things, payment service providers and pay-now-buy-later firms. With the shift to embedded finance and a rapidly evolving industry stack, banks will need to be agile if they want to remain commercially relevant.

I deliberately switched between consumer and customer, with consumers being a more general market participant and customers being a consumer with which a merchant has a relationship.

[ad_2]

Source link