[ad_1]

There are many statistics that say how the vast majority of product ideas either never see the market or fail to produce the desired returns.

I don’t want to discuss the accuracy of any of these statistics, but what I can point out from my 8+ years of experience in various product development roles is that every successful product is developed by following a product development process.

“But developing products means being creative! Why are you wanting to coerce me into some process that chokes creativity?” you may ask. Yes, product development is a creative endeavor, but creativity is not an end in itself.

What we look for when developing products is innovation, and

innovation = creativity + intent.

We need to channel our creativity so that we not only come up with interesting product ideas, but with ideas that can be formed into concepts and developed into a successful product that is relevant to the market. Such a process is a mix of highly creative work and mundane, even menial tasks. And all of them seek our attention. But our mental capacity as human beings is limited. That’s why morning routines are so important: if every day I have meaningful defaults that I never have to think about, I can use much more of my remaining mental capacity to work creatively.

This is where the power of the product development process lies.

The hallmark of the product development process is that, in each stage, it gives us a set of tasks we have to get done and that we could otherwise easily forget, but that are crucial for us to stay on the right track. The process provides us with a “meaningful default” blueprint—so that we, as humans, can better focus on the creative parts of product development.

And in this article, I am going to show you how.

What is product development, and what is the product development process?

Product development vs. product management

To give you the right context when talking about product development, and to avoid confusion, let’s start by answering the following question: what is product management, and what is product development?

Product management encompasses ALL activities around the product portfolio of a company.

Product development, in turn, is a part of product management, and focuses on developing product ideas into a marketable product. Its activities are coupled with the product development process of the company. This process starts when the company leadership decides, “Hey, let’s start developing a specific product!” and ends when the product enters the market.

Who is involved in the process?

The answer to this question is highly industry-, company- and product-dependent.

In a start-up, product development may consist of the founders and a few ad-hoc contracted people. In large product developments, such as the aerospace or medical industry, dozens of different departments with hundreds of people may be involved. And such huge products might consist of smaller standalone products that live within them and have to be developed themselves—think of ships with their lifeboats.

In any case, we must remember that going through a product development process is not only a process (a repeatable ‘recipe’ that shows us how to turn a bunch of ideas into a marketable product), but it is also a project.

Why? Because it fulfills the textbook definition of a project—“a one-time undertaking that is carefully planned to achieve a specific result (in our case; a specific, new product).”

And like any other project, it a) needs to be managed, and b) the key metrics you have to track are quality, budget, and schedule. Hence, company leadership appoints a project manager who at the same time serves as the product manager, because he will be the chief responsible for all product-related decisions (often even after the product has been brought to market).

The product manager then needs a product development team. This means that dedicated experts from various disciplines will work together and delegate specific tasks to their respective departments.

A typical setup will look like this:

For tracking the other 2 project metrics (quality and budget; timelines being chiefly tracked by the product manager), people from the quality department and the financial controlling department will join the team.

They’ll be joined by representatives of R&D, design, and any other department that is in charge of coming up with and developing product ideas.

For tangible products, purchasing will also be involved, because every physical product consists of materials or components that you are going to process and have to source from outside the company. The purchasing department is also the only department that should talk to suppliers.

Also required for developing tangible products is a manufacturing arm, as your company has to actually produce the to-be product. It is important to keep manufacturing in the loop from early on, so that they can plan the production in time.

Then, there’s logistics. Even if your suppliers will ship their materials to your door, you still need to move them on your premises as well as organize the shipment to your customers.

No matter what kind of product you’re developing, you’ll also need a marketing and sales department to forecast as well as drive demand for your (to-be) product, develop a suitable marketing strategy and/or marketing plan, and be your voice towards the customer.

Other departments, such as HR, IT, & Infrastructure or Security may also be involved, but only peripherally.

At last, company leadership is involved in the process:

Product development teams do (and have to!) enjoy a certain degree of autonomy, but at some point, it is the company leadership that has to approve (or at least acknowledge) product-related decisions, budgets, cost changes, technical changes etc.

Approaches to product development and idea generation

You may have noticed that “no one size fits all” is a recurring theme in this article.

Each product is different, and each company has its own culture, philosophy and approach towards doing things. Same holds true for each industry, market, or geography: software development for construction material distributors in Central Africa is different from building family cars in Europe.

That’s why product teams can be set up in many different ways; product developments can take anything from a few days to many years—and the plethora of tools, templates, and methods that a company can use for developing products are also different in each case.

I am going to present to you 3 established approaches for product development and also point out what they are good for.

The Design Thinking approach

If your (to-be) product is simple and low-cost, but needs to be innovative, you might like to incorporate design thinking into your development.

Originating from post-WWII thought schools on design, psychology and creativity, design thinking as a method was substantially developed by Tim Brown and his company “IDEO”. It gained more and more traction during the ’90s and ’00s and can nowadays be counted as an established and well-known approach to product development.

In a nutshell, design thinking is a multi-step procedure that emphasizes the dialogue between designers and the target audience, where the designers show their product iterations to the customer and use their feedback until the product is sufficiently well-developed.

The first stage (“problem space”) is about understanding a problem, observing it, and synthesizing that information in order to come up with ideas for innovation.

For example, I participated in a design thinking program in 2008 and our team’s task was to come up with innovations in the field of Asian instant noodles. Hence we went to Berlin’s “Chinatown” (the Kantstraße-neighborhood) and immersed ourselves into its shopkeeper scene. We not only purchased their instant noodles but talked with them and their customers. We observed what their shops, their offerings, and their lifestyles looked like. We tried to draw a comprehensive picture of the “Asian instant noodle”-scene in Berlin.

The second stage (“solution space”) of design thinking is about gathering ideas, prototyping, and testing.

I remember we discovered that pretty much all of the noodles were packaged in non-eco-friendly foils.

After prototyping our way through new ways of packaging the noodles, we once again went to “Chinatown” and approached the shopkeepers and their clients (our “target customers”) with our MVP (minimum viable product).

When using design thinking, keep in mind that it does not address the commercialization of the final product—and that’s why it’s suited best for low-cost undertakings, where you can focus on concept development without having to worry too much about the pricing or the cost side of your business analysis.

Lean product development

“Lean” is a business philosophy that stems from Toyota’s approach to manufacturing and has become increasingly popular in the western business world since the 1970s.

The key idea is that you want to create a “pull” from one manufacturing station to the other, increasing value from station to station and eliminating waste wherever possible until you reach a state of (seemingly) effortless “flow.” As lean manufacturing proved itself as a very good approach to manufacturing, companies tried to transfer its principles to other domains. (Who of us hasn’t received comments like “I love your idea, but couldn’t you make it more lean?”)

The kicker is: things that make sense in the lean manufacturing world do not make sense when transferred to the product development world.

For example, assembly lines have to work at close to 100% workload and close to 0% fault – else they are becoming a source of waste.

But, if a product designer or financial controller or test engineer is loaded to 100% with work, he cannot possibly deliver good results. He is drowning in work, which will certainly cause delays, and what’s more: in the case he receives even more tasks (“I need that engine drawing by end of day—it’s urgent!”), the effect only gets amplified.

The same is true for faults regarding mistakes: manufacturing on the assembly line is an entirely predictable process and should rightfully aim for 0% faults—after all, that is the point of mass manufacturing! Product development, on the other hand, has an element of unpredictability and is also a creative endeavour and must allow for mistakes, tinkering, and brainstorming ideas between product developers.

That’s why lean product development champions like Don Reinertsen have been working on a meaningful adaptation of lean principles for the product development world. I recommend his books (“Product Development Flow”; “Managing the Design Factory”) and videos to get a deeper insight on how lean principles can boost product development when correctly adapted and implemented.

Lean product development focuses almost exclusively on the “How” of your product development and is particularly well-suited for complex products where you can leverage its waste-reduction philosophy.

The New Product Development (NPD) framework

At last, I’d like to talk about the NPD-framework, whose characteristic is that it encompasses all aspects of a product development in a structured way, dividing it into phases.

And this is where we once again have a “no one size fits all”-moment: NPD can be structured in many different ways. You can easily come up with 10+ different and highly granulated stages of product development from start to finish, or use 3 or 4 stages of less detailed depth.

That’s why in our article, we will work with the following 6 stages of product development.

The 6 stages of product development

1. Ideation

Products don’t come into life out of thin air.

Designers, engineers, and other employees are always tinkering—working on new ideas, product concepts, process improvements, etc. I also have a personal example for you; in one meeting, a designer sitting next to me was bored by the speaker, so he started drawing a car dashboard in his notebook. It had nothing to do with our meeting, but still the designer was drawing it. It’s in any designer’s lifeblood.

Thus when the CEO of a car company says: “Today we are kicking-off the development of our new compact class SUV that should be ready for production in 48 months”, it is merely the starting signal to start phasing in all that existing material into the product development process.

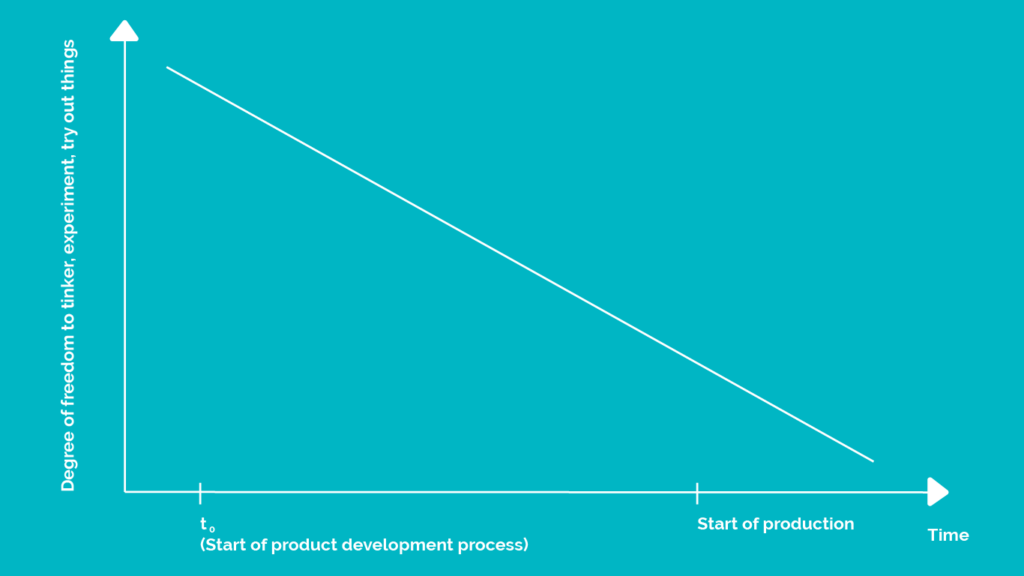

At the beginning of the article we have been talking about the trade-off between creativity and a formalized path to a product. If you can only take away one diagram from this article, let it be the following:

The earlier we are in our product development process, the more wiggle-room we have to experiment with ideas. And this room for tinkering is where the innovative stuff comes from. Use the early-stage to brainstorm, experiment and try out new product ideas. Later in the process, when the product is almost ready for manufacturing and shipping, there is much less room to experiment, and you can do so only at a high cost by scrapping everything you have developed until then.

That’s why the infamous Berlin-Brandenburg International Airport took so many years to build: in 2012, the airport was ready to be opened for public, and just days before its inauguration, they figured out that the fire protection system had to be re-designed as it would not work properly in case of fire. They had to re-work almost anything that had already been installed into the brickwork shell. As a result, the inauguration got postponed another 5+ times, the costs jumped to 7 billion(!) Euro (from initially planned 1.2 billion Euro) and the airport opened in late 2020 (construction works started in 2006)—and I have not met one traveller who likes using this airport!

2. Product definition

Once the new product development process starts, the first goal toward which all ideation is directed is to the so-called “product definition.”

Remember the “time-versus-decision-level” triangle? Just as a company’s leadership might kick off the new product development process with the rather vague “Let’s build a compact class SUV,” it’s now the product development team’s turn to further narrow down the parameters of the product. In our case, “compact class SUV” would mean looking at the current industry and market standards: 4200 mm long, 1600 mm high, 1800 mm wide, 100 kW engine power, four-wheel drive, seats for 5 passengers, 3 to 5 doors, etc.

This set of fundamental, hence “product-defining” decisions is quite final and sets the path for all future product-related decisions.

3. Prototyping & concept development

Once the to-be product is defined, prototyping must be ramped up.

Of course, some rudimentary prototypes will already have been built to help the product team shape and conceptualize the product definition. But, as prototyping is a time-intensive and costly business that requires many experts (somebody has to build these real-life looking clay models, interior mockups, 3D-drawings, etc.), it only makes sense to intensify it once you are clear on your product definition, from which you will create a selection of designs.

The first job of prototyping in this stage of the product development process is to build a selection of real-life models (each one representing a possible product concept) from which we will select one that we will develop into a marketable product.

4. Initial design

The first phase of prototyping will provide us with several possible designs of our product.

Now it’s the product team’s job to select one of them. This decision is important because it is a “do or die”-moment: after you decide upon one design, you have to invest in all the toolings you will need for assembly line production, you will need to close contracts with suppliers, you will need to build up your supply chain and, generally speaking, align all your stakeholders towards that specific to-be product.

Once you decide on one design, prototyping continues until product launch (which is the phase just before the start of production on the assembly line), but only within the model you have chosen.

5. Validation & testing

This is a stage that has to begin right at the moment you initiate your new product development process.

Why? In business, every decision has a cost and an opportunity, and you want to systematically reduce risk and increase opportunity as cleanly as possible. That’s why, for example, before you decide on a specific design, you want to validate and test your assumptions by inviting client focus groups to pass their opinions on those designs. And before you do that, your marketing department has to do its market research, discover customer needs, and prioritize the most relevant groups of potential customers that might be interested in such a compact class SUV. In my case, our team concluded that young families and “empty nesters” in Western Europe are our target market, and we centered our decisions around that assumption, trying to maximize our market share in these niches.

Remember: the more money you are about to spend on your product development, the more you have to think about how to test your assumptions and check their feasibility before actually spending the money.

6. Commercialization

Technically, commercialization comes last—before you can sell a product, you need to have one.

At the same time, the starting thought of any product development has to be: “If we build it, it’d better be profitable!”

That’s why, from the start, commercialization has to be at the core of all your decisions along the product development process.

Make it a habit to build a business case for each upcoming product decision, i.e. determine the investment and individual costs, estimate the pricing and the volume, and consider further risks that might arise.

If the result is positive, it might make sense to build in that product functionality. If the result is negative, it is likely that it is not a good idea to pursue it.

Every now and then, calculate the business case for the entire product as well.

This might also mean having to pull the plug in the middle of the process acknowledging: “Ok, we’ve already spent a lot of money, but continuing the project would mean only more costs without the realistic chance of a sufficient return on our investment.”

Sometimes, as a product manager, you have to be able to make unpopular decisions and know when they’re necessary.

A few last words of advice.

As we come to the end of this article, let me share a few pro secrets with you. Many product developers neglect them, which means that you will get an extra edge if you take them to heart.

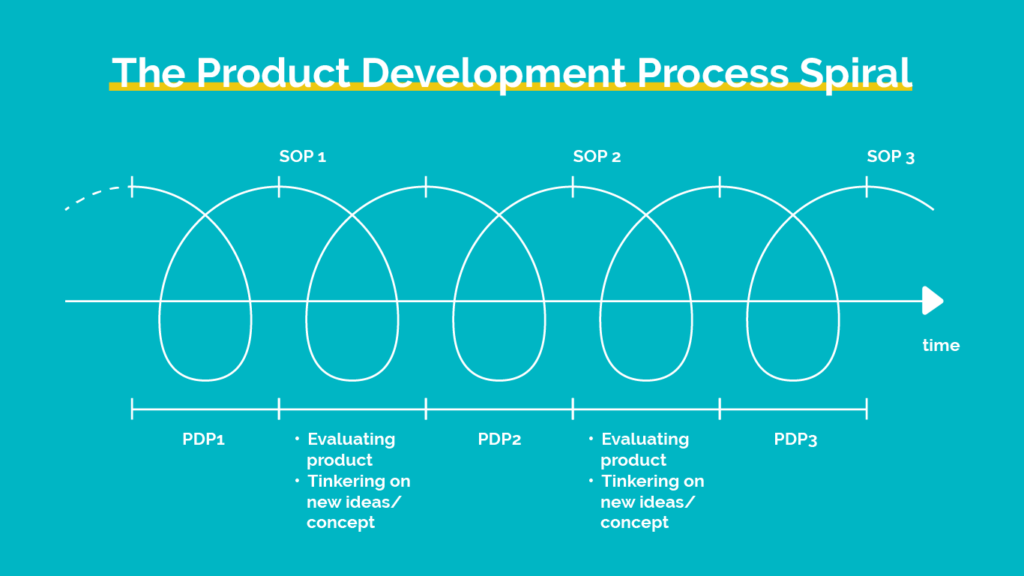

- The product development process might end with the start of production, but your product continues its way along the product lifecycle. Follow it and learn the hell out of it:

- How does your product perform in the market, in particular compared to your assumptions during development?

- Who is buying it, at which prices, and how do your customers use your product?

- What other customer feedback are you receiving? (“Shitstorm on social media”, anyone?)

- How can you use that information in your next product development cycle?

- What does this all mean for your product portfolio, your product development strategy, and the general value proposition of your product(s)?

- What type of product should you bring into market next?

- Collect and consolidate all the information you are gathering from the above questions, as well as all the lessons you’ve learned during the product development process. Nobody likes to put effort into a proper post-mortem (political reasons also play a part!)—but the rewards from actually comparing real world data of your finished product with all those assumptions you used in your SWOT analyses, case studies, idea screenings, etc. are priceless. Do that work!

- Remember that the moment your product enters the market, your job is not done—the successor to the product you just launched has to be better-developed than your existing products. Think about how to improve the product development process the next time: what methodologies to try out (or leave out). And then, act on it!

Wanna dig deeper? Check out the following material:

Don Reinertsen, The Big Ideas Behind Lean Product Development, The Lean Startup Conference 2013.

IDEO Design Thinking Portal.

Paul Lopusushinsky, A Guide To The Product Manager Career Path + Roles And Skills

Liked this article? Subscribe to our newsletter to get curated product management articles and resources delivered fresh to your inbox.

[ad_2]

Source link

![How to Create a Comprehensive How to Guide [+Examples]](https://wildfireconcepts-media.sfo3.digitaloceanspaces.com/2022/12/how-to-guide-1.jpgkeepProtocol-440x264.jpeg)